Capacity Planning for Data Warehouses and Lakehouses: Stop Guessing, Start Designing

If your current “capacity plan” is basically turn autoscaling on and hope the CFO doesn’t notice the bill, you’re flying blind.

Modern warehouses (Snowflake, BigQuery, Redshift) and lakehouses (Databricks, Snowflake, Synapse, etc.) make scaling easy — but easy to scale also means easy to overspend or underdeliver.

This guide walks through how to think about capacity planning like a data engineer, not a gambler.

1. Why Capacity Planning Still Matters in the Cloud

Cloud marketing: “Infinite scale, pay only for what you use.”

Reality:

- Queries queue at month-end close.

- Dashboards time out during exec reviews.

- Finance asks why your Snowflake/Databricks line item doubled… again.

Capacity planning gives you:

- Predictable performance: p95 latency and concurrency SLOs.

- Cost control: a sane upper bound on credits/DBUs/slots.

- Operational stability: fewer fire drills, more repeatable behavior.

Even with “serverless” or “auto” everything, you still need to design:

- How much you’re willing to pay at peak.

- How much performance users actually need.

- How workloads are isolated so one job doesn’t nuke everything.

2. Capacity in Warehouses vs Lakehouses

Let’s define what “capacity” really means in both worlds.

2.1 Core Dimensions of Capacity

For both warehouses and lakehouses, think in 5 dimensions:

- Compute capacity

- Cores / nodes / virtual warehouses / slots / DBUs.

- Determines how fast queries/jobs run.

- Storage capacity

- Compressed TBs in tables or object storage.

- Impacts scan cost and performance patterns.

- Concurrency

- Number of concurrent queries/jobs before queueing.

- Throughput

- Data processed per unit time (GB/s scanned, rows/s transformed).

- Cost envelope

- The hard constraint nobody wants to mention until the invoice hits.

2.2 Data Warehouse vs Lakehouse: How Capacity Shows Up

High-level comparison:

| Aspect | Classic Warehouse (Snowflake, Redshift) | Lakehouse (Databricks, Lakehouse on S3/ADLS/GCS) |

|---|---|---|

| Storage | Built-in / external, columnar tables | Object storage (Parquet/Delta/Iceberg) + metadata |

| Compute model | Virtual warehouses / clusters / slots | Clusters / job clusters / serverless pools |

| Separation of storage/compute | Usually yes | Yes (strong separation, often more explicit) |

| Autoscaling | Warehouse/cluster size & concurrency | Cluster autoscaling (min/max nodes), serverless options |

| Billing metric | Credits, slots, node-hours | DBUs, node-hours, job runs |

| Typical pain | Query queues, surprise credit spikes | Cluster sprawl, idle clusters, flaky tuning |

Key difference:

Warehouses hide more of the stack; lakehouses expose more knobs (cluster size, storage formats, shuffle behavior).

So capacity planning for lakehouses is closer to classic big data cluster planning, just with cloud elasticity.

3. Start with SLOs, Not Hardware Sizes

If you start with “What size warehouse/cluster do we need?” you’re already doing it backwards.

You should start with:

- p95 dashboard latency (e.g.,

< 5 seconds). - Max acceptable queue time (e.g.,

< 10 secondsfor business users). - Batch SLA windows (e.g., daily jobs finish by 6 AM).

- Monthly cost ceiling (e.g., “Analytics platform ≤ $X/month”).

Then capacity planning becomes:

How do we design compute, storage, and workload isolation so we hit these SLOs within the cost ceiling?

4. Understanding Workload Types (Your Real Capacity Drivers)

Most teams mix these workload types on the same platform:

- Interactive BI / Ad-hoc

- Many short-ish queries.

- Human-facing latency expectations (2–10 seconds).

- Highly spiky usage (stand-ups, exec meetings, MBRs).

- Scheduled ELT / ETL

- Batch pipelines (hourly/daily).

- Heavy scans, joins, window functions.

- Usually can tolerate higher latency but has a deadline.

- Data Science / ML

- Sampling, feature generation, model training.

- Irregular but often heavy and bursty.

- Back-office / bulk operations

- Backfills, reprocessing, historical rebuilds.

- Can be huge, and often poorly controlled.

Capacity planning rule:

Don’t mix these blindly. You size and isolate capacity per workload class, not per account.

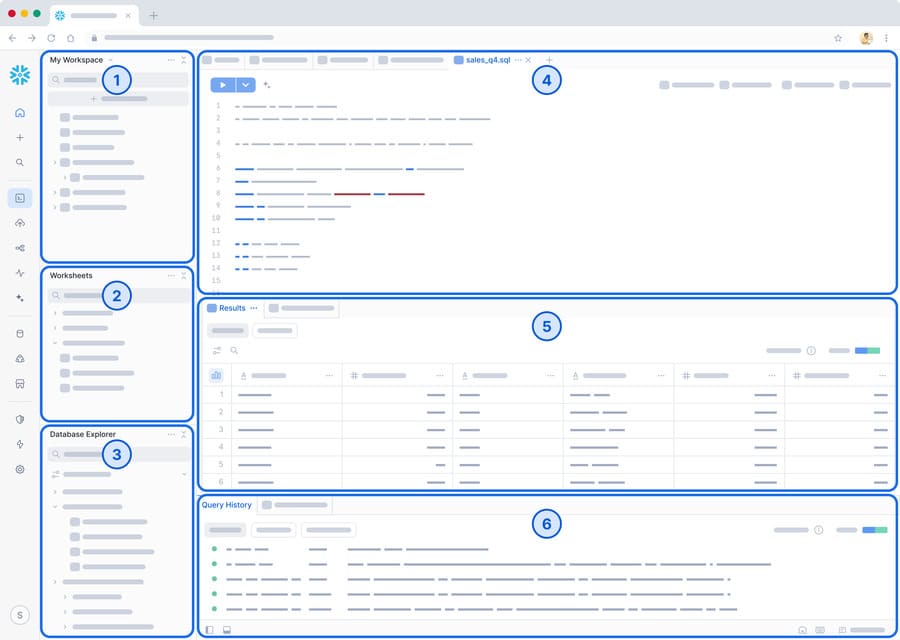

5. Practical Example: Snowflake-Style Warehouse Capacity Planning

(If you’re not on Snowflake, the logic still applies: translate “warehouse” to “cluster / pool / job cluster”.)

5.1 Step 1 – Pull Real Query History

Example: aggregate query history to understand peak concurrency & scan volume.

-- Daily concurrency and scan volume

SELECT

DATE(start_time) AS day,

HOUR(start_time) AS hour_of_day,

COUNT(*) AS total_queries,

APPROX_PERCENTILE(total_elapsed_time, 0.95) AS p95_runtime_ms,

SUM(bytes_scanned) / 1e9 AS gb_scanned

FROM snowflake.account_usage.query_history

WHERE start_time >= DATEADD(day, -30, CURRENT_TIMESTAMP())

AND query_type = 'SELECT'

GROUP BY 1,2

ORDER BY day, hour_of_day;

What you look for:

- Hours with high concurrency + bad p95 runtime.

- Hours with massive GB scanned (heavy pipelines).

5.2 Step 2 – Map Workloads to Warehouses

Example mapping:

BI_WH– small/medium size, autoscaling 1–4, for BI dashboards.ETL_WH– larger size, autoscaling 1–8, for nightly pipelines.DS_WH– medium, no autoscaling, for data science notebooks.

Goal:

- BI queries never queue because ETL is hogging compute.

- ETL has clear window + enough power to finish on time.

- DS has a sandbox that can be throttled without killing the business.

5.3 Step 3 – Estimate Required Capacity per Warehouse

For each workload:

- Peak concurrent queries (from history).

- Current p95 runtime vs target p95 runtime.

Rough heuristic:

If p95 latency is 2x slower than your target during peak, you likely need ~2x more effective compute for that workload (bigger warehouse and/or more clusters via autoscaling) OR better tuning (clustering, pruning, fewer “SELECT *”).

5.4 Step 4 – Translate to Cost

Estimate monthly cost:

-- Hypothetical: estimate monthly compute cost per warehouse

SELECT

warehouse_name,

SUM(credits_used_compute) AS monthly_credits,

SUM(credits_used_compute) * 3.0 AS est_monthly_cost_usd -- assume $3/credit

FROM snowflake.account_usage.warehouse_metering_history

WHERE start_time >= DATEADD(month, -1, CURRENT_TIMESTAMP())

GROUP BY 1;

Now you can ask:

- If we double BI_WH capacity at peak, how many extra credits is that?

- If we lower ETL_WH size and extend ELT window by 30–45 minutes, how much do we save?

This is actual capacity planning, not vibes.

6. Practical Example: Lakehouse (Databricks) Capacity Planning

Databricks-style thinking:

- Workloads are typically on job clusters or all-purpose clusters.

- You choose node type, min/max workers, and sometimes serverless.

6.1 Step 1 – Classify Jobs

From job runs history:

- Identify critical jobs (SLAs, business impact) vs nice-to-have.

- Group by:

- Frequency (hourly, daily, ad-hoc).

- Runtime.

- Data volume processed (input rows/bytes).

6.2 Step 2 – Right-Size Clusters

Common anti-patterns:

- Huge node types “just in case”.

- Clusters that sit idle between runs.

- Same cluster type for tiny and massive jobs.

For each job group:

- Use smaller nodes + more workers for shuffle-heavy jobs.

- Use auto-termination aggressively for sporadic jobs.

- Use job clusters per pipeline instead of one giant multipurpose cluster that becomes a bottleneck and failure domain.

6.3 Step 3 – Translate to DBUs and Cost

Estimate:

- Average runtime per job.

- DBUs per node type.

- Number of runs per period.

Then:

total_cost ≈ (DBUs_per_node_type × node_count × runtime_hours × runs) × $/DBU

Once you know cost per pipeline, you can decide:

- Which pipelines deserve more compute (shorter runtime).

- Which can tolerate less (cheaper, longer jobs).

7. Storage & File Layout: The Silent Capacity Killer

You cannot “capacity-plan” your way out of horrible storage design.

Common killers:

- Tiny files (millions of 1–10 MB files).

- No partitioning on large fact tables.

- “SELECT * FROM big_table” patterns everywhere.

- Lack of clustering / ZORDER / sort keys for common filters.

What you should do:

- Partition by usage patterns, not just by time.

- Example:

(country, date)instead of only(date)if queries always filter by country.

- Example:

- Compaction:

- Regularly compact small files into larger ones (256–1024 MB).

- Column pruning:

- Create thinner tables/views for BI if people only need 10 columns out of 200.

Good storage layout means:

- Less data scanned → less compute to hit same SLOs.

- Fewer retries/timeouts → more predictable capacity.

8. Best Practices and Common Pitfalls

8.1 Best Practices

- Define SLOs up front

- p95 dashboard latency, max queue times, batch deadlines.

- Isolate workloads

- Separate warehouses/clusters for BI, ETL, and DS/ML.

- Plan around peaks, not averages

- Use history to find true peak days (month-end, Black Friday, campaigns).

- Use autoscaling with sane limits

- Set min/max bounds that reflect cost limits.

- Continuously tune

- Indexing / clustering / ZORDER / partitioning.

- Query rewrites: avoid SELECT *, remove unused joins.

- Budget per domain/team

- Tag resources and allocate cost by business unit.

8.2 Common Pitfalls

- “Cloud is elastic” → no one owns capacity -> chaos.

- One giant warehouse/cluster for everything.

- Letting random “exploratory” jobs run unbounded on prod compute.

- No monitoring for:

- Queue time

- p95 and p99 latency

- Spill to disk / shuffle failures

- Ignoring backfills in planning (they often blow up your nicely-tuned capacity).

9. Quick Checklist to Build Your Capacity Plan

You should be able to answer all of these:

- What are our p95 latency targets for BI dashboards?

- What is the SLA for our main ELT pipelines?

- What is our monthly cost ceiling for the platform?

- How many distinct workload classes do we have, and are they isolated?

- What are our true peak hours/days?

- Are we over-provisioned (idle time) or under-provisioned (queueing, timeouts)?

- What are our top 5 heaviest queries/pipelines, and are they optimized?

If you can’t answer at least half of these, you don’t have a capacity plan — you have a credit card.

10. Conclusion & Takeaways

Capacity planning for warehouses and lakehouses is not about picking the “right” instance size once and forgetting it.

It’s about:

- Translating business expectations (SLOs) into compute & storage design.

- Segmenting workloads and giving each the right amount of isolation and horsepower.

- Instrumenting and iterating as data, users, and usage patterns grow.

The platforms make scaling easy. That’s exactly why your job is to put guardrails and intent around that power.

Call to action

Next step:

- Pull your last 30–90 days of query/job history.

- Identify top 3 pain points (slow dashboards, flaky pipelines, or cost spikes).

- Design one concrete change in your capacity layout (e.g., new BI warehouse, separate ETL cluster, better partitioning) and measure its impact.

Do that a few cycles in a row, and you’re doing real capacity planning — not just reacting.

Image Prompt (for DALL·E / Midjourney)

“A clean, modern data architecture dashboard showing capacity planning for data warehouses and lakehouses: multiple compute clusters, storage layers, and workload lanes (BI, ETL, ML) with different sizes and utilization, minimalistic, high-contrast, 3D isometric style, dark background, neon accents.”

Leave a Reply